Originally published in The Blade on Sunday, December 24, 2006

By RYAN E. SMITH

BLADE STAFF WRITER

Imagine being around for that first Christmas.

Or the first Hanukkah.

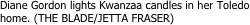

Diane Gordon can’t boast of either of those. But she does remember the very first Kwanzaa.

It was 1966, and she was “truly amazed” by what she heard about a new African-American holiday modeled on African harvest celebrations, focusing on things like unity, faith, and ancestral pride.

The next year she was celebrating at a relative’s house in Toledo, but it wasn’t easy. Kwanzaa had just been created. There were no books on it at the library, no supplies or ritual objects for sale at local stores.

“Most of the information we could not even find in Toledo,” Mrs. Gordon said.

Nevertheless, friends and family crammed into her aunt’s house on Delaware Street to learn about Kwanzaa together.

“We were like sitting on top of each other,” said Mrs. Gordon, who taught herself all about the holiday’s traditions and songs and then passed it on to the rest of the group.

“All of it was new,” the Old West End resident said. “I would learn and then when I presented [it to the group], I would ask them to repeat everything.”

As African-Americans around the nation prepare to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Kwanzaa, which begins Tuesday, they also reflect on the significance of the secular holiday, how much it has changed, and its role among a new generation of blacks.

Back in 1966, the country was first introduced to the brainchild of Maulana Karenga, now a black studies professor at California State University, Long Beach.

The idea for a uniquely African-American holiday took root at a time when European colonials had just been dislodged from Africa, and the world was coming to realize that the continent had a history and culture worthy of note, according to Apollos Nwauwa, interim director of Africana Studies at Bowling Green State University.

African-American leaders engaged in the civil rights movement here were looking for a way to connect with their original homeland and show their cultural heritage. Kwanzaa became a codified way of doing that, he said.

What began as small celebrations in pockets of homes now have become a holiday noted by millions — and counting.

“I think it’s going to gain a lot of momentum,” Mr. Nwauwa said. “Those who were celebrating it at that time, they were radical scholars and cultural nationalists. Now, it has moved beyond that to a celebration of culture.”

The term Kwanzaa comes from a Swahili phrase meaning “first fruits of the harvest” and many of its traditions were derived from first harvest celebrations in Africa. Swahili words are at the heart of the vocabulary of the holiday, which takes place from Dec. 26 to Jan. 1.

There is a feast on Dec. 31 and gifts, usually expected to be educational or cultural, are given on the last day of Kwanzaa.

Renee Walton, of West Toledo, always looks forward to Kwanzaa and begins preparing about a week in advance. She and her husband, Otis, have been celebrating since 1968.

“We love it,” she said. “We thought it was so exciting because for once there was something that black people could come together and call their own.”

These days, they do it to pass on important lessons to their grandchildren. Every Kwanzaa, they gather as a family to remember where they came from — opening the front door, lighting candles, and calling out the names of ancestors who have passed on. “We want our grandchildren to grow up knowing who they are and what they’re about and they come from a strong legacy of strong black people,” Mrs. Walton said.

They also stress the importance of the holiday’s principles as guides to a good life. Those seven principles are: unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity, and faith.

At the center of many Kwanzaa gatherings is the kinara, a candleholder. There is one candle for each principle.

Rahwae Shuman, of the Old West End, remembers making his own kinara from the wooden rocker of a chair and a few nails when he started celebrating the holiday in the mid ’70s.

“I used that kinara before Kwanzaa became commercialized,” he said. “In those days, we were pioneers. ... We’d bring food to each other’s homes. It was a very simple thing.”

Times have changed. Now there are Kwanzaa greeting cards and there’s even been Kwanzaa postage stamps.

Many celebrations have moved out of the intimacy of the home into larger, communal gatherings.

(Locally, Toledo Kwanzaa House is sponsoring events each day of the holiday at the Wayman Palmer YMCA on 14th Street. Programs begin at 7 p.m. and the doors open two hours earlier. Mrs. Gordon is the group’s coordinator.)

Kwanzaa may be a little different now, but it’s just as relevant as ever for Mr. Shuman.

Its principles, he said, contain the keys to salvation for the nation’s blacks, who must become more self-reliant in the wake of incidents like Hurricane Katrina and the government’s poor response to help its predominantly black victims.

His wife, Msimbi, an educational consultant who grew up in Kenya, has found the holiday’s traditions a welcome reminder of home. Moreover, she said they’ve helped bring African-American contributions to the mainstream and proven a good means of breaking down racial barriers.

“Just sharing Kwanzaa with different cultures and different races, it is a good vehicle for having dialogues that are non-threatening,” she said.

And, no less important, it can be a vehicle for fun.

Students in Jacqulyn Houston’s fifth grade class at Stewart Academy for Girls in Toledo didn’t know much at all about Kwanzaa before they started learning about it this year.

Now, they love it, even as they try and pick up its difficult lingo. (You try saying “kujichagulia,” Swahili for “self-determination.”)

“It’s fun,” said student Brionna Witcher. “It’s just a happy time for family and friends to get together.”

Perhaps the most important thing they’ve learned about the holiday, to their great relief: “It’s not to take the place of Christmas. It’s in addition,” Mrs. Houston said.

Kwanzaa may not have the history of other holidays celebrated at this time of year — Christmas celebrations go back more than 1,500 years and the tradition of Hanukkah is even older — but that doesn’t matter to people like Mr. Shuman.

“Culture is dynamic, and it’s very rare to actually witness during your lifetime a major addition to a culture,” he said. “To those people who say it’s made up, it is a created holiday, but so is every American holiday that they celebrate.”

African harvest celebrations inspire holiday

KWANZAA PRIMER

WHEN IT OCCURS: The annual festival lasts seven days, from Dec. 26 to Jan. 1

MEANING: The word Kwanzaa comes from the phrase, “matunda ya kwanza,” which means “first fruits of the harvest” in Swahili. It is modeled on the first fruit celebrations of ancient Africa.

HISTORY: Kwanzaa was created as a cultural festival in 1966 by Maulana Karenga, now a black studies professor. Its purpose was to encourage African-Americans to think about their African roots and develop a higher African-American consciousness.

SEVEN PRINCIPLES (NGUZO SABA):

• Umoja — Unity

• Kujichagulia — Self-determination

• Ujima — Collective work & responsibility

• Ujamaa — Cooperative economics

• Nia — Purpose

• Kuumba — Creativity

• Imani — Faith

RITUAL OBJECTS & SYMBOLS:

• Mkeka — straw table mat, on which all other objects are placed

• Mazao — crops, symbols of the fruits of collective labor

• Muhindi — one ear of corn for each child, symbolizing fertility

• Kikombe cha umoja — the unity cup, used to perform the libation ritual

• Zawadi — gifts, traditional items that encourage success

• Kinara — candleholder, a symbol of ancestry

• Mishumaa saba — seven candles, one for each of the seven Kwanzaa principles

CUSTOMS: Each night, the family gathers to light the candles of the kinara, lighting another candle each day of the holiday. A traditional feast is held on the night of Dec. 31. Gifts are usually opened on the last day of Kwanzaa, Jan. 1.

SOURCE: www.beliefnet.com