Originally published in The Blade on Sunday, March 2, 2008

BY RYAN E. SMITH

BLADE STAFF WRITER

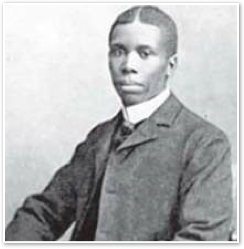

Paul Laurence Dunbar, an internationally renowned poet and the first African-American to make it as a professional writer, always will be associated with his hometown of Dayton.

That’s where Dunbar was born and where he published his first volume of poetry. It’s where he died and where his home in 1936 was made into a state memorial, making it the first shrine in America established by a government institution to honor a black man.

It was Toledo, though, that put Dunbar on the map.

The friendship and financial support of locals such as attorney Charles Thatcher and Dr. Henry A. Tobey led to the writer’s second book of poetry being published here, and it was that work, Majors and Minors, that brought Dunbar fame.

“It was that second book that ended up getting the exposure that he probably would have never gotten here in Dayton,” said LaVerne Sci, site manager for the Dunbar House State Memorial.

Born in 1872 to former slaves, Dunbar was the only African-American in his high school class. He is best known for his verse using black dialect — though he also wrote in standard English — and for being a dignified voice of the disenfranchised.

“He catches the essence of the African-American community,” explained Herbert W. Martin, a Dunbar scholar and professor emeritus from the University of Dayton who went to high school and college in Toledo. “It’s not stereotypical at all, though some people think that the dialect makes them stereotypical.”

For a time, Dunbar worked as an elevator operator in Dayton, struggling to sell his first book of poetry to his riders. What really launched his career was when he met Thatcher and Tobey, superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital, a facility for the mentally ill.

Both men admired his work, set up opportunities for Dunbar to read his writings in town, and eventually underwrote the cost of publishing his second book of poems, Majors and Minors, in 1895.

That volume, published by Toledo’s Hadley & Hadley Printing, came to the attentionof the influential literary critic William Dean Howells, thanks to a playwright who was in Toledo at the time. His glowing review in Harper’s Weekly, specifically of Dunbar’s use of dialect, put the poet on the road to celebrity.

“The real coup was that William Dean Howells said that it was really first-rate poetry and that makes Dunbar’s reputation,” Martin said.

Dunbar’s reception by the progressives of Toledo — including social reformer mayors Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones and Brand Whitlock — provides a glimpse into what a dynamic place the city was at the time, according to Timothy Messer-Kruse, chairman of the ethnic studies department at Bowling Green State University who wrote an article about Dunbar’s Toledo connection for Toledo’s Attic, an online repository of Toledo history (www.toledosattic.org).

In the article, he describes an exclusive literary meeting that Dunbar attended while in town when another speaker talked about the laziness and lack of ambition he witnessed among blacks in the South. Dunbar’s rebuttal that night was his own writing and elocution, a performance that was highly praised.

“Part of the remarkable thing about Dunbar’s life is how he is able to negotiate what is truly an impossible climate of racial discrimination. This is one of the most horrific periods of racial repression in America,” the BGSU professor said. “I think it indicates the cosmopolitan and progressiveminded character of some of Toledo’s leading artist and literary lights.”

One of Dunbar’s biggest champions was Tobey.

“Dr. Tobey really regarded him as a talented person and not just a colored man,” said Sci, of the Dunbar House. “As a result, Dr. Tobey took an interest in Dunbar that was much like being more than a mentor, almost thinking of Dunbar as a son. He was so proud of him.”

While Dunbar wrote on all matter of themes and in many formats — including plays, novels, essays, and short stories — he once wrote to Tobey that one of his ambitions was “to be able to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that after all, we are more human than African.”

The notoriety Dunbar achieved after his second book led him to travel to England and later he landed a job at the Library of Congress. Tragically, he died of tuberculosis in 1906 at the age of 33.

Today, Dunbar’s name lives on not just in his literary works.

A legacy of naming schools for him took root as well. Sci said it’s easy to see why: “He symbolized personal industry. He symbolized determination. He symbolized the strength to dream and explore new heights.”

BGSU has a residence hall named for him, and in Toledo, the Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy, a charter school that opened in 2002, continued the tradition of honoring the poet.

Part of the reasoning, according to school leader Thomas L. Williams, had to do with his local ties.

“It’s very important to honor him...,” he said. “He basically did get his literary start with the support he got out of his Toledo connections.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar. (OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

Toledo helped shine light on gifted black poet