BY RYAN E. SMITH

BLADE STAFF WRITER

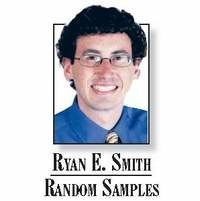

My Dad died last week, but I can still picture him.

He was a jolly, joking, larger-than-life presence anywhere he went, and he was easy to love. He revelled in telling stories, whether it was to his family or the stranger standing next to him in line at the grocery store. Sometimes the words wouldn't come out quite right - like when he'd say, "I think I had a crotch in my computer" or "I just can't phantom that" - but the words always came. It embarrassed us as kids, but I miss it now.

I'll never forget one of the last pieces of advice that he gave me: "Never get old." At the time, hearing his words made me sad. It was hard watching his decline from boisterous to barely-there, the victim of a little-known disease called Lewy body dementia that eroded his body and mind over the last few years. His words seemed like a permanent reminder echoing in my head of how a 68-year-old man can seem so much older than he should.

Later, though, I came to see his advice as an affirmation of the way he'd always lived his life, going all the way back to his days as a child growing up in a very modest household. That's when he, along with a favorite cousin, was dubbed a vilde chaya - "wild animal" in Yiddish - by my grandmother for the frenzy of fun they had together.

My Dad never had the means to finish college, and he had to work hard to make his 42-year-long career in the insurance industry a success. Still, he always managed to approach his job with joy - both because he believed in the good it did for his clients, who often became his close friends, and because he sometimes managed to sneak in a nap on the floor of his office or catch a matinee at the movie theater next door.

You could call my Dad an eccentric. He was a man who allowed me to paint bloodshot eyeballs on the garage door, who loved driving a motor home that he nicknamed The Bugwacker, and who made home videos while on vacation pretending to be a reporter for W-S-M-I-T-H.

My Dad made it to all 50 states - 48 of them in the motor home - and he forced us to take a family photo on the side of the road as we entered each one. When we were too tired or too cranky, he'd get out all by himself, set up a tripod, adjust the camera's timer, and take a picture just of himself. He did it because these trips were as exciting to him as they were to us.

There was a passion in him to live, really live, and you could tell from the way he went all-in on anything that he tried. This was true of the little things, like collecting M&Ms memorabilia, which take up a whole corner of our house, and of the big ones, like his devotion to family, friends, and clients.

I'd never deny that my Dad was different, but he was no Peter Pan. He'd seen the worst that life could throw at a man, including the death of a teenage son to cancer and several of his own close calls with the hereafter. The trick is that he never let it take that glimmer from his eyes or the mischievous smile from his lips.

Even after my Mom - his secretary for more than 15 years and life partner for 35 - couldn't care for him at home anymore, even after the feeding tube was necessary, even after all the trips to the emergency room, he continued to show glimpses of his true self. He charmed the nurses, hopped into other people's empty beds just to be feisty, and continued to make friends every day with the earnestness of a kid on a playground.

That's what my Dad meant by never growing old, and that's some advice I plan on taking.

Originally published in The Blade on Friday, January 29, 2010

RANDOM SAMPLES

Gary Smith